Just because there is a currency collapse, martial law, or a natural disaster, that does not mean you can ignore medical needs.

What will you do when there are no bandages, no medications, and no way to get help?

Even if there is only “weeds”, trees, and moss around, you may have a number of useful medicinal aids at your disposal.

Learning how to recognize natures medical resources is a very important part of preparing for a crisis. Aside from simply reading a few books and going on a few field trips, take the time now to make sure you know how to prepare specific treatments in a range of situations.

How to Use Nature’s Medicines

As someone with a keen interest in herbal remedies and natural medicines, I concluded long ago that it is truly difficult to remember all the incredible healing resources in nature. It is truly to your advantage to gain hands on experience and keep a well organized journal that contains detailed information on both the resources and how to use them. This journal should be treated with as much care as other sources of information such as maps and anything else that you consider indispensable to long term survival.

If you choose to keep a copy on your computer, do not forget that it may no longer be accessible if you do not have access to electricity. A good medical journal may span several hundred pages and may also be quite thick from pressed specimens, however it is well worth its weight.

In time of need, you would truly be amazed at how confusing a sketch or even a photo may look when compared to a specimen that you can see and touch for a closer comparison.

Taking courses in how to use natural medicines is critical if you expect to know what you are doing in time of need and be successful. No matter whether you study online or actually attend wilderness medical excursions, do not simply put the materials aside once you are done with the courses. Always make the information part of your personal wilderness medicine journal and try to practice making medicines and equipment as much as possible.

Herbal Remedies for Chronic Illnesses

Most preppers already know that good quality medical care is essential for preserving health, managing injuries, and ensuring that the next generation of humans can be born and grow to maturity.

Many people also realize that in a major crisis or social collapse, medical care will be unavailable. Critical medications such as antibiotics and other drugs will be even more important in the post-collapse world. Even though you, and others may already know about herbal remedies and may also know how to grow and prepare them, that does not mean your work is done.

Consider a situation where you have been growing garlic, ginger, turmeric, and other herbs that can be used as herbal antibiotics. Perhaps you have even made oils from these herbs or dried them out for later use. Now let’s say a major crisis occurs and you cannot get home for several days in order to retrieve your stash of herbs, or worse yet, your stash gets ruined while bugging out. In these situations, not knowing about the local wild plants in your area can spell disaster.

Here are some things you can do right now to ensure you will always be able to find and prepare the wild herbs in your local area for medicinal needs:

- Get a field guide that features pictures and descriptions of medicinal herbs in your local area. The guide should give you full details about where they grow and also how to recognize them. The guide should also give you a listing of plants that are commonly mistaken for the plants you will need for medicinal purposes.

- Make a list of all herbs that may be of interest to you. Do not list herbs that are from rare species or ones that are listed as endangered.

- Go to sites where you can find the plants you identified as useful for your needs. Once you find a good sized patch of herbs to work with, take samples of leaves, stems, roots, flowers, and any fruit the plants may bear. These small samples should be done for all four seasons and folded into your journal. You can also take pictures of the leaves and other parts of the plant, print them out, and keep them with the actual samples. In your journal, also make note of the spot where they are growing and the basic characteristics of the area.

- Find a local herbal specialist or Cooperative extension and ask an expert to confirm that you have all the plants labeled correctly.

- Once you have confirmed that your listings are all correct, you can begin looking for other places where these herbs grow well, and also start learning how to prepare them for medicinal needs. If at all possible, try to gather seeds from the wild plants. If you have to bug out or move to another area, you can try planting these seeds indoors and see if you can get them to grow.

In a major crisis, it is entirely possible that you will wind up traveling hundreds of miles as part of a massive evacuation form a dangerous area. Since there is no telling where you will wind up, you will need to use some additional methods for spotting medicinal herbs. You can try keeping field guides on hand.

One way to expedite the process of finding medicinal herbs in foreign locations is to see if you can find ones related to herbs that you already know about. Herbs that grow in other regions may be more or less potent than the ones you are used to. Make sure that you know how to test herbal potencies for your own safety and well being.

Non-Herbal Remedies for Skin and Wound Management

No matter whether you are trying to find your way out of the city, navigate through a woods, or move objects from one place to another, injuries are bound to happen. During a major crisis, you can also expect infectious diseases to increase because of poor sanitation and increased risk of exposure to infected individuals.

In many cases, wounds that you would normally pay little attention to may become infected and require direct application of antibiotics. If you are moving through unfamiliar areas, you can also expect increased problems with wounds because your immune system may not be as well adapted to the exact strains of pathogens in the area.

Here are some natural remedies that you can apply directly to skin and wounds:

1. Honey – even though honey has a sweet taste and seems very mild, it is one of the most powerful antibacterials you can find. It has been used successfully on both oral and skin wounds for centuries without major side effects or other problems. If you are able to find a beehive, be very careful when gathering the honey. Since while honeybees are at very high risk for extinction, try to take only as much honey as you need, and try to avoid breaking apart the entire hive. You should also do your best to subdue the bees with smoke instead of killing them.

2. Sphagnum Moss – Since sphagnum moss contains iodine, it will work well as an antibiotic. You can usually find this moss in bogs or other marshy areas.

3. Salt Water – If you are near an ocean coastline or other source of salt water, you can spray salt water onto wounds as a form of antibacterial. Do not rub the wounds with the salt water. Instead, try to run the salt water over the wounds similar to taking a shower. Before using salt water, you should also filter it and boil it to make sure it is as clean as possible.

4. Tannic Acid – If you have rashes, blister, sores, boils, or other skin ailments, tannic acid may be of use. You can obtain this acid from boiling acorns, and also from nutgalls that form on oak trees.

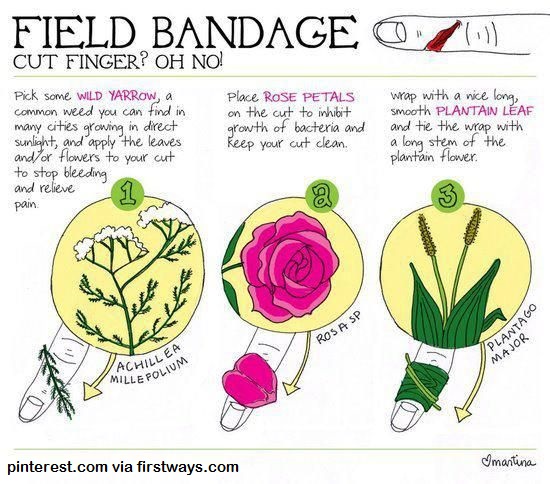

Splints and Bandages

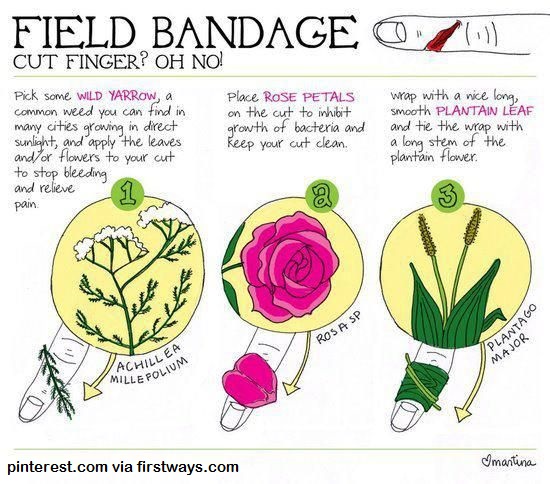

To make bandages, non-poisonous leaves can be used to put pressure on the cut, and also to protect it from the elements. The best leaves to use are from the Plantain plant. If you chew on the leaves to release liquid from within the leaves, you will also have a natural antibiotic in the form of mashed leaves to put on the wound. From there, just use a second leaf to wrap around the crushed Plantain and the wound.

Some fungus that grow on oak and silver birch trees may also be safe to use for bandaging. Since it is notoriously difficult to tell safe fungus from poisonous ones, be sure to ask a local expert on mushrooms, molds, and mosses so that you know what to look for. As with locating and identifying useful herbal remedies in a woods or field, be sure to take samples and photos for your journal of useful organisms as well as ones that it may be confused with.

Splints for broken bones and injuries can be made from just about any tree branch. To keep the splint in place, make rope from yucca leaves or any other leaf that has strong, straight fibers in the leaf.

If these plants are not available, tree bark from smooth bark trees can also be used. In order to avoid friction burns and abrasions, use mullein leaves (or any other non-toxic leaf) as a cushion between the splint and the the body part being immobilized.

In order to make a splint from a branch:

- Choose a branch that is long enough and wide enough to support the area that needs to be immobilized. The finished splint should also be long enough so that the joint above and below the injured area will also be immobilized.

- The branch should be as straight as possible and of even thickness for the required length. You can use a branch that is bent or curved, but try to use the straightest area parallel to the injured area.

- Try to avoid branches that show signs of fungal growth, insect damage, or anything else that might increase the risk of developing an infection.

- If you have sharp enough knife, try to smooth out the rough areas of the branch so that it is as smooth as possible. You may also want to flatten out the splint so that there is a wider surface area. Just make sure that all areas that you cut are covered so that your skin does not come in contact with the unseasoned wood.

- When placing a splint, make sure that the rope or cord is not too tight or too loose. A wrapping that is too tight can cut off blood circulation and lead to further problems. If the wrapping is too loose, the splint will move around and cause more abrasions. A loose splint will also fail to support the injured area and keep it properly immobilized.

- Remember that if you have a broken bone or a dislocated joint, splinting the injured area is only a temporary fix. You will still need to find a competent medical professional to move the bone or joints back into place. Unless you have taken courses and practiced bone and joint setting, it is best to leave these matters to a doctor. A broken bone or dislocated joint can still be near blood vessels or nerves that are still intact. The last thing you will want to do is try to manipulate the broken or dislocated areas and wind up causing damage to other tissue in the area.

Tourniquets and Wound Packing Materials

When you have a deep wound, or one that is bleeding heavily, you may need to use several different methods to stop the bleeding and then make sure the wound is protected. Once you address the most immediate problem, you may still need other items from nature to ensure that the wound is managed as well as possible.

1. Tourniquets – When blood is spurting or pouring form a wound limb, there is no time to prepare a bandage let alone a wound filler. Your first job may well be to cut off the blood flow as quickly as possible using a tourniquet. Just about anything that can be wrapped tightly between the wound and the heart can be used.

For example, if you are in a meadow or field, tall grass or straw can be twisted together quickly and wrapped above the wound. Anything that is pliable enough to wrap, and then twist will work to form a tourniquet.

Remember that you must be able to loosen and tighten the tourniquet every few minutes in order to avoid gangrene. If you only have straw or other relatively weak stalks or even tree bark to work with, you may need to make several tourniquets to manage the injury.

2. Pressure Bandages – If you have an abdominal wound, or some other wound that cannot be isolated using a tourniquet, you will need to make a pressure bandage. Once again, just about anything will do as long as you can apply pressure without completely stopping blood flow. You can try taking several leaves from safe plants and roll them up to form a pad large enough to cover the wound.

If soft, absorbent leaves such as mullein are available, use them close to the wound, and then stiffer ones on the outer layer. From there, use your hands, or even a flat rock to hold the leaves in place and apply additional pressure. Remember that as with a tourniquet, it can take several minutes for pressure and blood clotting factors to finally stop the bleeding. Try to make additional bandages from leaves so that you can apply new ones as needed.

3. Cauterizing Agents – If you are bleeding from a major artery, then it is possible you will need to burn the wound so that it stops bleeding. While cauterizing carries many risks, those problems can be dealt with later on. If you are bleeding heavily, stopping it needs to be your first priority. Even though you may not have access to metal in the woods, you can still build a fire and heat up rocks (after you remove soil and debris from them) that can be applied to the wound. Be very careful about the rocks you choose, as they can explode when heated, or just as bad, have poisonous chemicals that will get into the wound.

In a sense, choosing rocks for cauterizing, and other medical needs is not so different from choosing herbs. You will need to know a good bit about the geology of the area and the chemical makeup of rocks and their inclusions. For example, if you found a nice, flat piece of gray shale, that does not mean the entire rock has the same chemical composition. It may have some hidden parts that have toxic chemicals that will move out of porous areas of the rock when it is heated.

As with herbal remedies, try to obtain a comprehensive field guide that gives you detailed information about rocks in the local area and how they are most inclined to form and mix together. Next, go out and collect as many samples as you can. Bring your samples to a local geologist and ask him/her about which rocks can be safely heated up and used for medicinal needs such as cauterizing. If you can find a geologist or rock hound that has a special interest in hiking or natural medicine, then he/she may be a more viable source of information.

4. Wound Fillers – After you stop a wound from bleeding, there may still be large holes that need packing in order to prevent further damage. Here are three substances that you can use. While some require more preparation than others, at least you will have some options to choose from based on the materials available.

- Pine Sap – warm up the sap so that it is soft and sticky. Aside from having antibacterial properties, pine sap will protect the wound and will also stop the bleeding.

- Calcium Alginate – if you happen to be near a bed of kelp, or brown algae, you can extract calcium alginate from the leaves. When applied to a large or open wound, the moisture from the wound will cause the calcium alginate to form a protective gel. As with cauterizing, you still run the risk of developing a serious infection of the wound is not managed properly or if the calcium alginate does not all form up into a gel. That being said, this substance can also help stop blood flow, and may be of value if you have the time to prepare it.

- Sphagnum Moss, Leaves, and Other Soft Materials – Non-toxic mosses, leaves, and even grass can be used to pack wounds and keep them from reopening. If you must use leaves, try to find herbs to mix in that also have antibacterial properties.

Makeshift Syringes

Chances are, if you are working with herbs or other natural medicines, there may not be much need to inject substances into the bloodstream. Nevertheless, it may still be necessary to isolate insulin from animal sources to treat diabetes, or other injectables that require some kind of syringe or needle. If you think about the basic parts of a syringe, you may be surprised to find that there are quite a few ways to make a makeshift version from natural materials.

- The Needle – to work effectively as a makeshift syringe needle, the material used must be very thin, strong enough to resist breaking when puncturing the skin, and hollow. Some possible sources of needles include wasp and hornet stingers (do not use bee stingers because they are barbed), fine porcupine quills, and very thin reeds. If you are going to use insect stingers, make sure that the all of the venom is removed from the stinger.

- The Barrel – this is where the medicine will be held until injected into the bloodstream. Just about any rigid, hollow stem from a non-toxic plant will do. Thicker reeds, bamboo stem, and other dried, durable stems can be used for this purpose. To attach the needle to the barrel, you may need to set the needle at an angle so that there is less chance of breaking it. Next, you can seal off the space between the needle and the barrel with pine pitch or some other natural glue like substance.

- The Plunger – anything from a well trimmed tight fitting small branch to a solid, rigid plant stem can be used for the plunger. Just bear in mind that the plunger must fit snugly inside the barrel so that the medicine is pushed through the needle instead of squirting out the back end.

Some problems that you may encounter when using a makeshift syringe:

1. It will be very hard to make exact dosage measurements. If you have a way to determine how much material is ejected from the needle, then you can try making notches in the barrel and the plunger so that you can make a reasonable estimate. Before you go into a crisis situation and run out of syringes, make it a point to know exactly how much liquid should be discharged with each dose. You can do that with a measured syringe now, and then make a circle representing that amount in your journal. If possible, try also allowing one single dose to stain the page so that you can observe the size of the liquid stain on a known paper source. Make sure that you have an additional blank page so that you can make comparisons in the field. Do not forget to make these comparisons for herbal or animal based injectables that you may need to prepare from scratch.

2. Even though you may be able to get medicine to move through the needle, you may not be able to create enough of a vacuum to pull medicine into it. You will be best served by creating a simple leaf funnel or using some other means to pour the medication into the syringe.

Once you are able to make needles in a wilderness setting, do not overlook applications other than injecting medicines.

Solid needles can be used to stitch wounds (using animal sinew, fibers from plants) and also for acupuncture. Today, even conventional medicine includes acupuncture as valid treatment for pain and other ailments.

As long as you know how to sterilize the makeshift needles and where to apply them, there are plenty of ways you can use this remedy as part of your wilderness survival kit.

Crutches and Carriers

When it comes to making improvised medical supplies, crutches are probably some of the easiest to make. If you are in a wooded area, simply pick a branch or tree limb that has a fork at one end. Try to pick one with the widest angle possible in the fork so that your armpit has a larger surface to rest on.

Next, use leave and vines/makeshift cordage to create a cushion that will fit under your arm. If possible, add an absorbent top layer of leaves so that the padding does not all become soaked with sweat. You may need to change the pad often for the sake of comfort and to avoid infections. When cutting the wood for the crutch, make sure that it fits comfortably.

If you are in a group, those who are injured may slow down the entire group. Rather than leave people behind or take a risk on not getting where you need to go, try making a litter or other form of carrier. Adults and children can be dragged along far easier than they can be carried. You can make a simple carrier using the following basic instructions:

- Take 2 saplings or branches that are about 1/3 longer than the height of the person who needs help being transported. Next, take 2 more saplings that are a little longer than the shoulder length of the individual. If the person is very heavy, or you do not have durable materials to make a mat with, then collect 2 or 3 more of the shorter branches.

- Use vines, bark rope, or other cordage to tie together the saplings. The longest saplings should be parallel to each other. Set one of the shorter branches at one end of the longer branches, but leave a few inches so that the bottom of the longer branches is the only thing that will be touching the ground.

- Set the second shorter branch at the opposite end. There should be just enough room between the top and bottom for the person to lay down without his/her feet or head flopping over the frame. You should also have enough room at the top of the litter to pick up the longer branches and drag them along.

- Add the remaining branches between the top and bottom ones. Try to make them equal distances apart. When you are done, the frame of the litter should look something like a ladder with the longer sides extending out further than the “steps”. Alternatively, you can also have the longer branches aligned so that they cross in front of the area where you will be standing. You may need longer branches for this method.

- Next you will need to add padding to the litter. Moss, leaves, and anything soft can be used for this purpose. You can also use vines to tie the materials down and make a more compact bedding. You can also used animal hides as long as they are well scraped and have been drying for at least a few days. Choose leaves and other materials that are as dry and clean as possible.

- If you have enough materials to make additional cordage, create a belly band or harness that attaches to the handles of the litter. You can use the harness to drag the litter and keep your hands free or pull along with your hands if you so choose.

- Unfortunately, in nature, there are not many ways to reduce friction on the bottom of the litter where it can catch on rocks, stumps, and many other things that will make it harder to drag along. You can try attaching very smooth, flat rocks to the impact areas.

Animal Based Remedies

Many people do not study animal based medicines because they think that plants are more diverse, easier to find, and easier to harvest. On the other hand, some of the most powerful and useful medicines are harbored within “dangerous” animals that you may already be hunting for food.

Study Ayurvedic and Chinese medicine to learn how to prepare medicines from these animals. It should be noted that there are a number of newer drugs based on compounds found within these animals, however it may be difficult to find out how the important molecules are isolated. Given that the Chinese traditional healers, Indian practitioners of Ayurvedic medicine, and Native American medicine people may have been using these animals to reliably treat illness, they are your best source of information on this matter.

Here are a few animals you can ask about as long as they are relevant to the local area for you and the practitioner has direct knowledge of the species of animals in the area:

- Frogs – produce natural antibiotics on their skin. Some frogs also produce neurotoxins and other poisons that may work in lower doses as painkillers and muscle relaxants.

- Pit Vipers – aside from carrying compounds in their venom that work as ACE Inhibitors (used to treat high blood pressure), snake venom may also be used as an anti-coagulant, to treat heart failure and preserve kidney function in diabetics. While venoms vary from one species of viper to another, local and indigenous medicine people may still know which animals can best suit your needs as well as how to safely milk the vipers of venom without killing them.

- Gila Monster – if you happen to be in the desert and need a stimulant to produce insulin, venom from these lizards may be of some use.

- Spider Venom – some species of spiders and tarantulas produce venom that can treat cancer, reduce pain,and relax muscles.

- Spider webs – as fragile as spider webs look, they can act as a strong, gentle network that allows flesh to grow back into place.

- Cone snail – if you are near a body of saltwater or near the ocean, cone snail venom may be an option for treating pain, managing heart disease and preventing epileptic seizures.

- Horseshoe Crab – if you aren’t sure if a bacterial infection is present, expose water, food, or other materials to the blood from a horseshoe crab. If the blood becomes thick and coagulates, then you know a dangerous infection is present.

- Centipedes – centipede venom can be used as a painkiller.

- Scorpion Venom – this venom can be used to treat cancer and also as a painkiller.

Poison Antidotes

Chances are, you already know that activated charcoal is one of the best antidotes for swallowed poisons. As long as you have trees and a fire, you can make charcoal as a form of poison antidote. To get the most out of the charcoal, crush it up and mix with water.

While some people recommend mixing tannic acid with charcoal, researchers have found that the tannic acid is actually absorbed by the charcoal, thus making less room available to remove the poison. If you need to draw poison from a wound, you can try using a charcoal poultice. Mud poultices and some herbal poultices may also draw poisons out of a wound.

Some modern research suggests that honey badgers, squirrels, and opossums have molecules in their blood that can neutralize venom from snakes, spiders, and other venomous animals that you might encounter. As with other animal remedies, try asking indigenous people in the area about how they treat venomous bites, and if they use preparations from these animals.

If you already know how to hunt these animals and use them for food, then you may already be on your way to an important natural remedy for venomous bites.

Worldwide, thousands of people die each year from consuming poisonous plants or mushrooms, getting bitten by venomous animals, or ingesting poison from some other source. While activated charcoal can help in some cases, there is very little else in nature that can act as an antidote.

You can still try to mitigate the effects of some poisons if you know what you came in contact with and how it affects your body. Once again, you should never experiment with these ideas. Take them to a certified herbalist or other practitioner of Chinese or Ayurvedic medicine to see if they already have experience with these methods.

For example, if you know that you have been bitten by a snake whose venom acts as an anti-coagulant, it may be possible to wash the site with some herb that has the opposite effect, but will not interact in ways that multiply the effects of other parts of the venom.

If you need to induce vomiting, warm salt water can be used for that purpose. Try to avoid herbs (unless you know they are safe to take with the poison in question) that induce vomiting because they can also interact with the poison and make it more dangerous. As a means of last resort, you can still try and focus on herbal or animal based remedies that counter the effects of the poison.

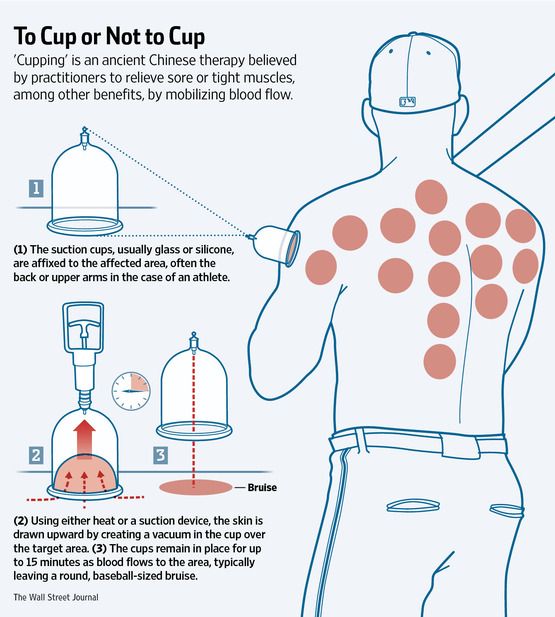

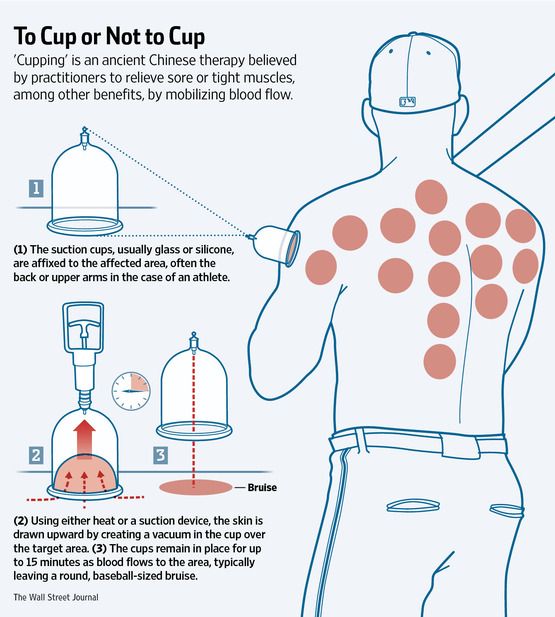

Fire Cupping

In ancient Chinese medicine, Fire Cupping was often use for pain relief. This particular treatment basically relied on creating suction by heating a round, hollow object, and placing it on the skin.

If you can generate heat and suction as in fire cupping, then you may be able to create a makeshift venom removal kit. Some things you might try using for the “cup” include hollowed bones, or mud that has been shaped into a bowl with a narrow opening and fired. Needless to say, if you have, or find a small glass bottle or a cup, then you can use that to for suction purposes.

If you can generate heat and suction as in fire cupping, then you may be able to create a makeshift venom removal kit. Some things you might try using for the “cup” include hollowed bones, or mud that has been shaped into a bowl with a narrow opening and fired. Needless to say, if you have, or find a small glass bottle or a cup, then you can use that to for suction purposes.

When choosing natural materials to make a fire cup, choose items that:

- Can easily be fashioned into a small, round cup with a narrow neck. If you cannot create a rounded cup, a longer, narrower form will do as long as the neck is still narrower than the body.

- The cup should be able to retain heat well. If the material loses heat easily, it will not generate sufficient suction. The material should be able to retain the heat for at least 3 – 5 minutes.

- If you are going to keep an open flame on the cup while in use, it should be non-flammable.

- You can try boiling a wooden cup, however it may not work as well as other materials.

Rocks for Generating Steam

From winter colds to spring allergies, and other respiratory ailments, inhaling steam or herbs mixed with steam is often the best remedy. While this may seem like a novel idea, generating steam for these purposes is possible using natural resources. As with heating rocks to cauterize wounds, you need to be very careful about which rocks you use and how you use them.

Here are some important things to keep in mind:

- When rocks are heated, they can crack or break apart causing sharp projectiles to fly all over the place. Porous rocks are usually the most problematic because water from rain, dew, and other sources seeps into the rock. Once the rock is heated by a fire, the water turning into steam will create pressure that causes the rock to break apart.

- Heated rocks can also emit gasses that are poisonous. It does not matter if the rock is porous or not, since even surface contaminants can emit poisons when heated.

- When you pour water onto hot rocks, the sudden changes in temperature can also cause the rock to fracture or explode.

- As hot water seeps into the rock, it can mix with other chemicals hidden deep in the pores. These chemicals will escape with the steam and can be poisonous if you inhale them.

- Because rocks very so much in composition and formation, you need to work with a reputable geologist in your local area in order to help reduce the risk of choosing rocks that can cause more harm than good.

- When creating a steam bath, many people try to keep the steam in an enclosed area. Never put yourself in a position where the materials used does not allow adequate ventilation. For example, never use plastics or any kind of tarp that does not allow air to flow through it. It is better and safer to take the time to create a leaf or bark mat then wind up suffocating in a steam bath. When choosing plants to make the covering, make sure that you wash and dry them thoroughly so that you do not pick up stray chemicals that can be harmful if inhaled with the steam. Only work with plants that you know to be safe and non-toxic for this purpose.

- Never use steam sweats unless someone else remains outside the steam area and can monitor you for signs of trouble. This includes making sure that you exit the steam area every few minutes so that you do not dehydrate or suffer from heat stroke/exhaustion.

Leeches and Maggots

When science was in the process of overtaking religion for control of the masses, the use of leeches and maggots was dismissed as quackery. Today, modern doctors have had to substantially revise their opinion on the use of these animals as part of sound medical treatment.

Here is how you can use leeches and maggots in time of need:

- Leeches can be used to suck blood from serious injuries. Basically, if you had to sew up a limb that was amputated or almost amputated, or some other injury that caused damage to the blood vessels, the blood will pool and slow down healing. If you apply leaches for a few hours each day, they will absorb the blood pool and allow the veins to heal.

- Historically speaking, leeches were often used in “bloodletting” for colds, and many other diseases. At this time, it is believed these therapies do more harm than good. That being said, if you need to stimulate blood production, sucking out small amounts may actually do more harm than good.

- Maggots are used to manage deep infections where the flesh is rotting or is very close to that stage. To use maggots for this purpose, simply let flies rest on the wound. Once the eggs from the flies hatch, they will become maggots that eat up the rotted flesh. Once you see blood an feel pain from the wound, then you know it is clean. Wash out the maggots and let the wound continue to heal.

In these times, we are often led to believe that there are very few, if any alternatives to modern medicine. Throughout the world, indigenous people have been using medicines for thousands of years from items found in nature. While herbal remedies are the most commonly discussed treatments, there are truly many other medicinal wonders that nature has to offer.

As a prepper, you should learn all you can about wilderness medicine and how to use it in a time of need. Aside from courses aimed at basic treatments, also consider studying indigenous methods so that you can expand your skill sets even further and utilize more materials in different geographic settings.

This article has been written by Carmela Tyrell for Survivopedia.

Now we’re getting down to the good stuff.

Now we’re getting down to the good stuff.